“Manila’s Finest” delivers on the promise of its trailer: a beautifully mounted portrait of 1960s Manila that feels more elegiac than nostalgic.

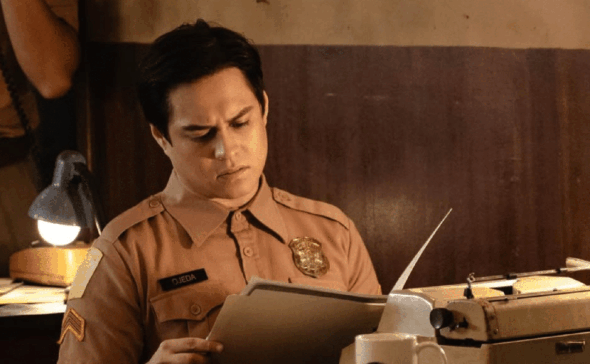

Director Raymond Red painstakingly recreates the period with care, from police uniforms and jeepneys to the rhythm of the streets.

Watching it feels like flipping through an old, dusty family album, lingering on images of a city that once was.

Set in 1969, the film unfolds during a time of growing unrest: student activism, political uncertainty, and shifting power within the police force.

It does not rush.

Red allows the film to move at its own pace, urging the audience to sit and feel the moment and reflect on what has been lost, the city, the people.

At the center is Piolo Pascual’s Captain Homer Magtibay, a chain-smoking, vinyl-loving policeman who appears upright and dependable, but slowly reveals a life shaped by compromise.

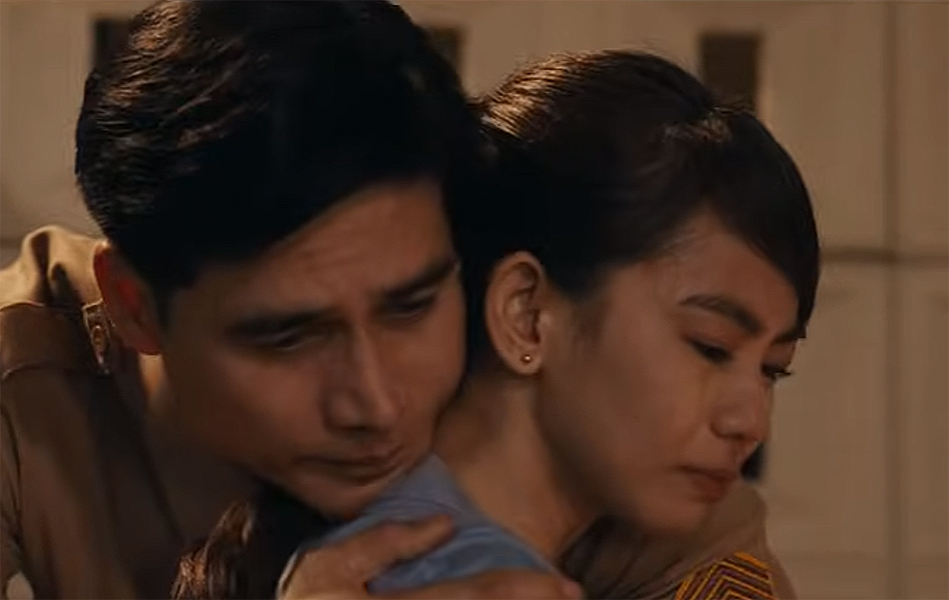

His strained relationship with his activist daughter, played by Ashtine Olviga, anchors the film emotionally, offering its most human conflict: a father realizing he stands on the opposite side of his child’s ideals.

Olviga is sincere and grounded, though her character, like many others in the film, feels underdeveloped.

Pascual plays Magtibay with restraint and vulnerability, resisting the era’s expected machismo.

Enrique Gil’s younger officer represents change pressing from within, while Rico Blanco’s corrupt police chief borders on caricature yet embodies institutional decay.

The supporting cast—Ariel Rivera, Cedrick Juan, Kiko Estrada, Romnick Sarmenta, Joey Marquez, Dylan Menor, Rica Peralejo, Soliman Cruz, and Jasmine Curtis-Smith—adds texture, though most are given limited room to deepen their roles.

Visually, the film is at its strongest. The cinematography and production design are impressive, bathing scenes in hues that recall faded photographs.

Written by Michiko Yamamoto, Moira Lang, and Sherad Anthony Sanchez, and backed by MQuest Ventures, Cignal TV, and Spring Films, the film carries undeniable pedigree. Yet the story never quite matches the richness of its setting. Despite compelling elements—corruption, power struggles, personal betrayals—the narrative feels a tad too muted.

Still, “Manila’s Finest” lingers. It reminds us that the unrest of the 1960s is not distant and that today’s indifference may be its most unsettling evolution.

Beautiful to look at and thoughtful in intent, the film may not have fully realized its potential but it leaves behind a quiet, uneasy reflection that stays with you.